Gatherers is the missing piece of the Stream API. So far, if we were missing a terminal method, we could always implement one ourselves by leveraging the Collectors API. This made parallel-collectors happen, which extend the capabilities of parallel streams.

However, what if someone wanted to implement a custom intermediate operation? While most of those you could shoehorn into the Collectors API, it has one major limitation – Collectors evaluate the whole Stream without any short-circuiting. This is precisely what Gatherers are for.

More about them in the upcoming article, but today we’ll go through a case study of implementing an efficient Gatherer that takes N last Stream elements (think limit() but from the other side).

This example is not about short-circuiting; it’s about implementing an intermediate operation efficiently without materialising the whole stream first.

Implementing Gatherers

Implementing Gatherers is similar to implementing Collectors, but with one major difference – the Integrator:

public interface Gatherer<T, A, R> {

Supplier<A> initializer();

Integrator<A, T, R> integrator();

BinaryOperator<A> combiner();

BiConsumer<A, Downstream<? super R>> finisher();

}Integrator is what allows signalling up that a Stream should stop pushing new elements by returning a boolean indicator:

boolean integrate(A state, T element, Downstream<? super R> downstream);

However, in our case, we’ll not be leveraging this.

Our goal is to implement a gatherer that returns the last N elements of a given Stream:

Stream.of(1,2,3,4) .gather(last(2)) .forEach(...); // 3, 4

Now, we’ll go through a few iterations: start simple, and then see what we can do to make it perform better.

Step 1: Make it Right

Probably the easiest way to end up with something that produces correct results is to use a List to accumulate the last N elements and update it whenever new elements arrive.

Firstly, we need to initialize our accumulator:

@Override

public Supplier<ArrayList<T>> initializer() {

return ArrayList::new;

}Then, we need to implement the Integrator with a core logic:

@Override

public Integrator<ArrayList<T>, T, T> integrator() {

return Integrator.ofGreedy((state, elem, ignored) -> {

if (state.size() >= n) {

state.removeFirst();

}

state.add(elem);

return true;

});

}And finally, we need to push those elements downstream in the finalizer:

@Override

public BiConsumer<ArrayList<T>, Downstream<? super T>> finisher() {

return (state, downstream) -> {

for (T e : state) {

if (!downstream.push(e)) {

break;

}

}

};

}And now together:

public record LastGathererTake1<T>(int n) implements Gatherer<T, ArrayList<T>, T> {

@Override

public Supplier<ArrayList<T>> initializer() {

return ArrayList::new;

}

@Override

public Integrator<ArrayList<T>, T, T> integrator() {

return Integrator.ofGreedy((state, elem, ignored) -> {

if (state.size() >= n) {

state.removeFirst();

}

state.add(elem);

return true;

});

}

@Override

public BiConsumer<ArrayList<T>, Downstream<? super T>> finisher() {

return (state, downstream) -> {

for (T e : state) {

if (!downstream.push(e)) {

break;

}

}

};

}

}Profiling and Benchmarking

Let’s try to benchmark and profile our creation. We’ll use JMH and async-profiler (conveniently integrated into JMH nowadays).

Here’s our benchmark (the full setup can be found on GitHub):

@Benchmark

public void take_1(Blackhole bh) {

Stream.of(data)

.gather(new LastGathererTake1<>(n))

.forEach(bh::consume);

}And here’s our result:

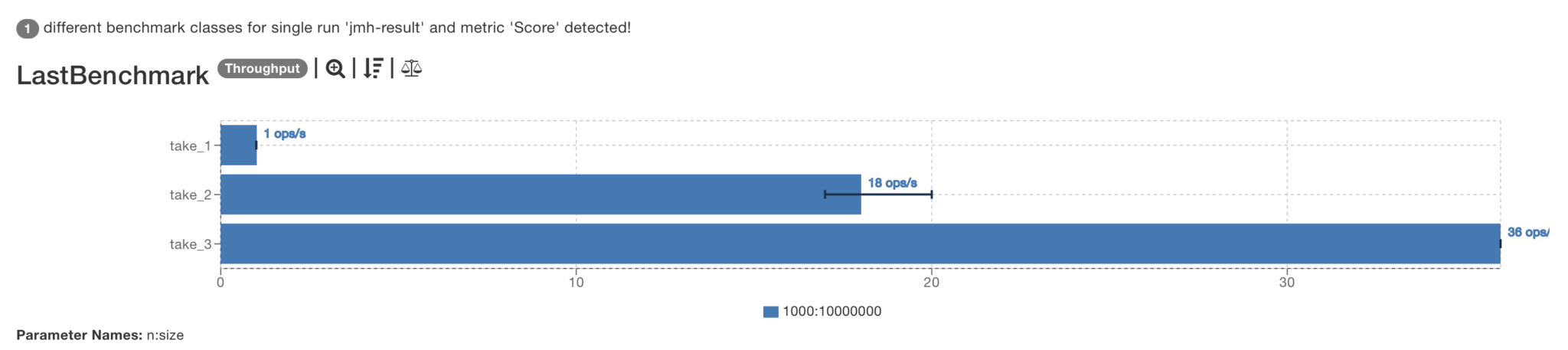

Benchmark (n) (size) Mode Cnt Score Error Units LastBenchmark.take_1 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 1,338 ± 0,239 ops/s

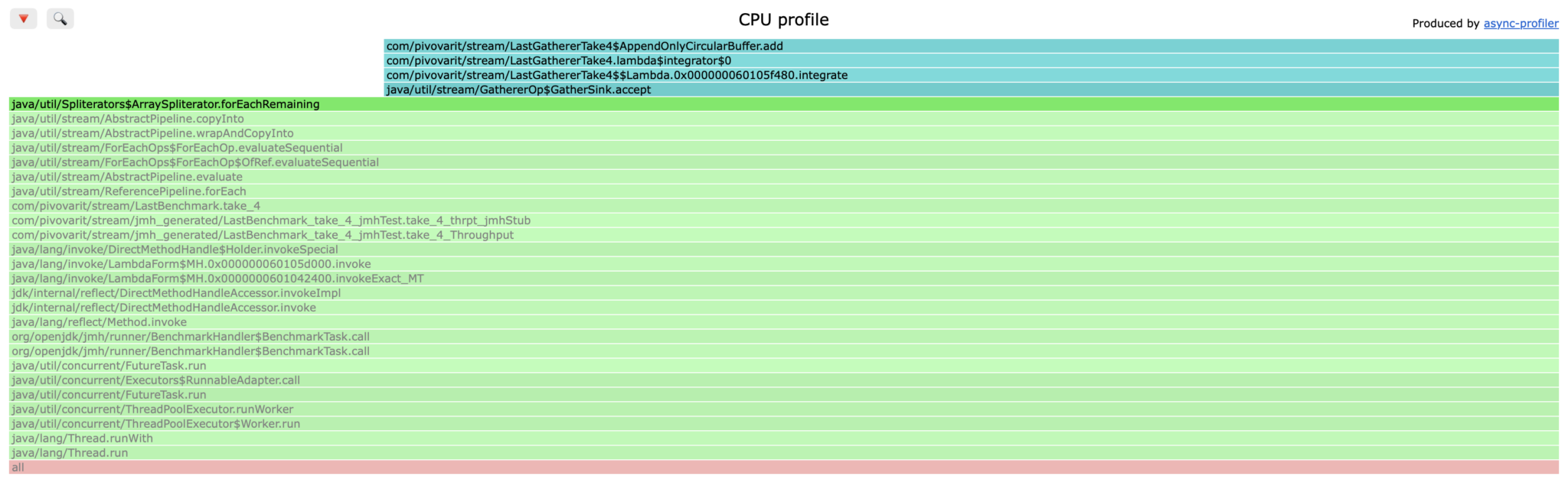

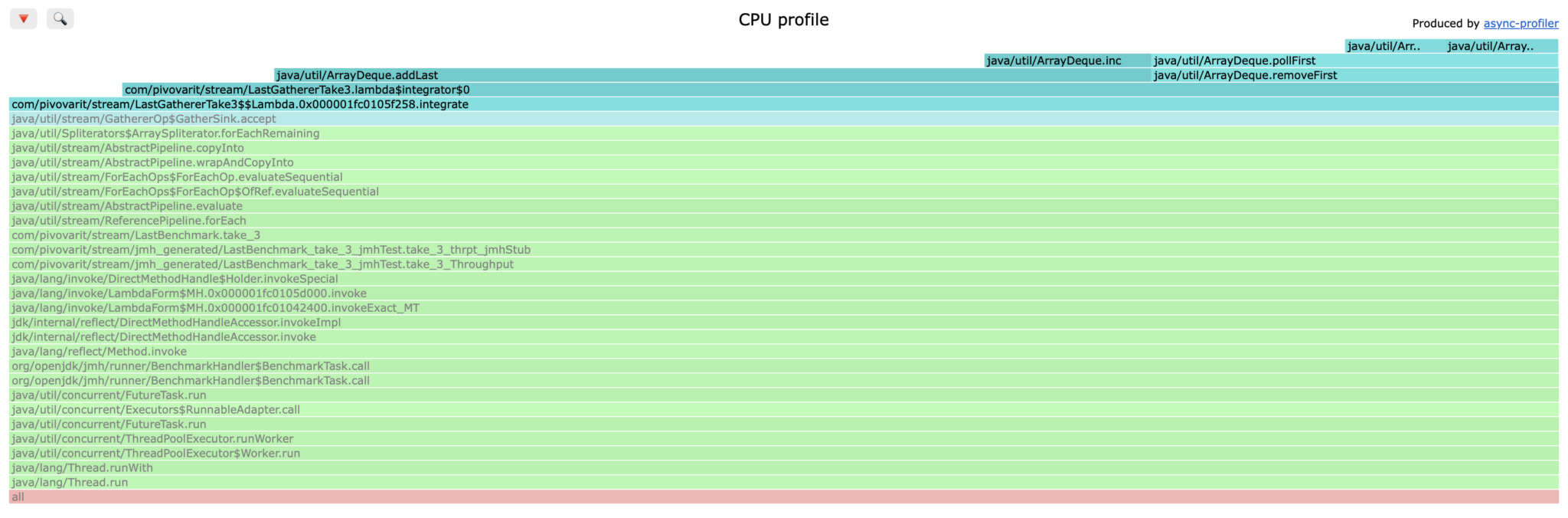

Is this good or bad? Probably good enough for most use cases, but… if you look closely into the flamegraph, you will see that the ArrayList#removeFirst() method takes significant portion of processing time!

In newer JDKs

removeFirst()exists via sequenced collections, but forArrayListit’s effectivelyremove(0)which does a relatively expensive array copying

Let’s remove the bottleneck!

Step 2: Make it Faster

From the above data, it’s clear that removal takes much more time than addition, so let’s address it. The easiest way is to simply buffer all results in a List, and then simply iterate through desired elements:

public record LastGathererTake2<T>(int n) implements Gatherer<T, ArrayList<T>, T> {

@Override

public Supplier<ArrayList<T>> initializer() {

return ArrayList::new;

}

@Override

public Integrator<ArrayList<T>, T, T> integrator() {

return Gatherer.Integrator.ofGreedy((state, elem, ignored) -> {

state.add(elem);

return true;

}

);

}

@Override

public BiConsumer<ArrayList<T>, Downstream<? super T>> finisher() {

return (state, downstream) -> {

int start = Math.max(0, state.size() - n);

for (int i = start; i < state.size(); i++) {

if (!downstream.push(state.get(i))) {

break;

}

}

};

}

}Let’s run our benchmarks again!

Benchmark (n) (size) Mode Cnt Score Error Units LastBenchmark.take_1 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 1,348 ± 0,201 ops/s LastBenchmark.take_2 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 19,052 ± 7,252 ops/s

Wow, the new implementation did ~15 times better! It’s something!

Flamegraph has also drastically changed, now it’s the ArrayList.add method that dominates, and we can see that this is mostly due to internal ArrayList.grow method that internally allocates a larger array (roughly 1.5× the previous size) and copies all existing elements into it (arrays can’t be resized).

Similar problem was the core issue of the previous bottleneck – removal of the first item from ArrayList involves copying the whole array content and shifting it by one! (ironically, the internal ArrayList method is called fastRemove()).

We’re an order of magnitude faster, but still inefficient. The original idea wasn’t that bad – we just used wrong data structure for it!

Step 3: Use the Right Data Structure

Maintaining a fixed-size buffer was not a bad idea, but it required a dedicated data structure which allowed efficient insertion/removal on both ends. ArrayDeque (double-ended queue) is one of such data structures.

If we take the code from step 1, and swap ArrayList with ArrayDeque, we get something like this:

public record LastGathererTake3<T>(int n) implements Gatherer<T, ArrayDeque<T>, T> {

@Override

public Supplier<ArrayDeque<T>> initializer() {

return ArrayDeque::new;

}

@Override

public Integrator<ArrayDeque<T>, T, T> integrator() {

return Integrator.ofGreedy((state, element, ignored) -> {

if (state.size() == n) {

state.removeFirst();

}

state.addLast(element);

return true;

});

}

@Override

public BiConsumer<ArrayDeque<T>, Downstream<? super T>> finisher() {

return (state, ds) -> {

for (Iterator<T> it = state.iterator(); it.hasNext() && !ds.isRejecting(); ) {

if (!ds.push(it.next())) {

break;

}

}

};

}

}And here are benchmark results:

Benchmark (n) (size) Mode Cnt Score Error Units LastBenchmark.take_1 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 1,340 ± 0,032 ops/s LastBenchmark.take_2 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 17,685 ± 33,776 ops/s LastBenchmark.take_3 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 35,751 ± 3,629 ops/s

Whoa! We’re doing twice better than the previous attempt!

Could we find even more bottlenecks?

At first sight, there are no obvious candidates, but… what if we could get rid of that removal altogether?

Step 4: Roll out Specialised Data Structure

What if we could avoiding paying the price of removals by introducing overwriting semantics?

The standard library doesn’t have a data structure like this, so we’ll need to roll out our own!

One of data structures with such properties is circular buffer – it’s a fixed-size data structure which overwrites oldest entries on overflow, and it’s quite easy to implement:

static class AppendOnlyCircularBuffer<T> {

private final T[] buffer;

private int endIdx = 0;

private int size = 0;

public AppendOnlyCircularBuffer(int size) {

this.buffer = (T[]) new Object[size];

}

public void add(T element) {

buffer[endIdx++ % buffer.length] = element;

if (size < buffer.length) {

size++;

}

}

public void forEach(Consumer<T> consumer) {

int startIdx = (endIdx - size + buffer.length) % buffer.length;

for (int i = 0; i < size; i++) {

consumer.accept(buffer[(startIdx + i) % buffer.length]);

}

}

}In this implementation an array serves as storage and an additional index is used to keep track of the position of the last element. We also need an extra int for keeping track of the actual buffer size.

Let’s see it in action!

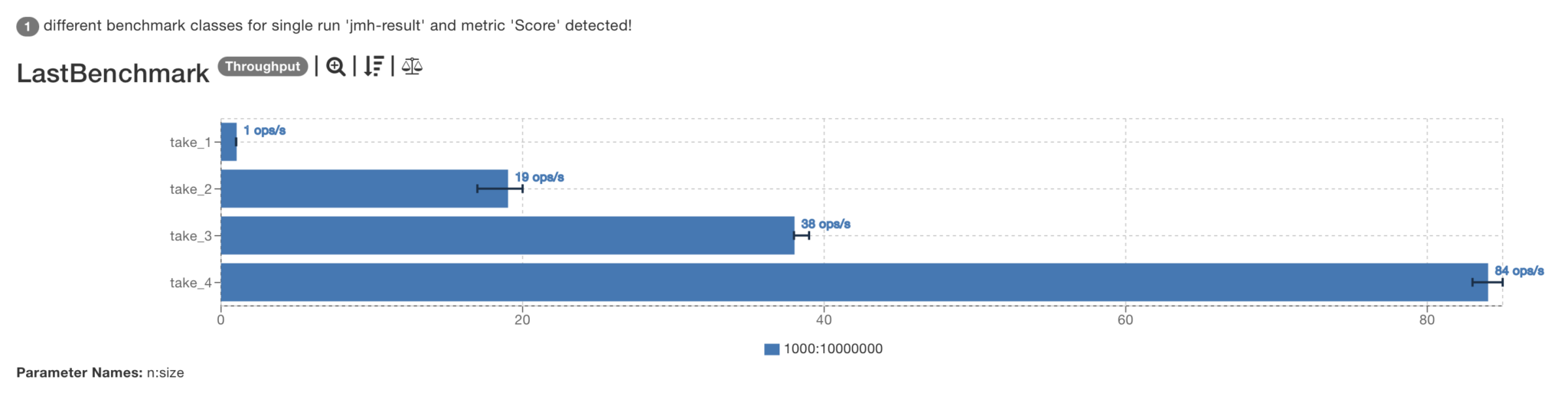

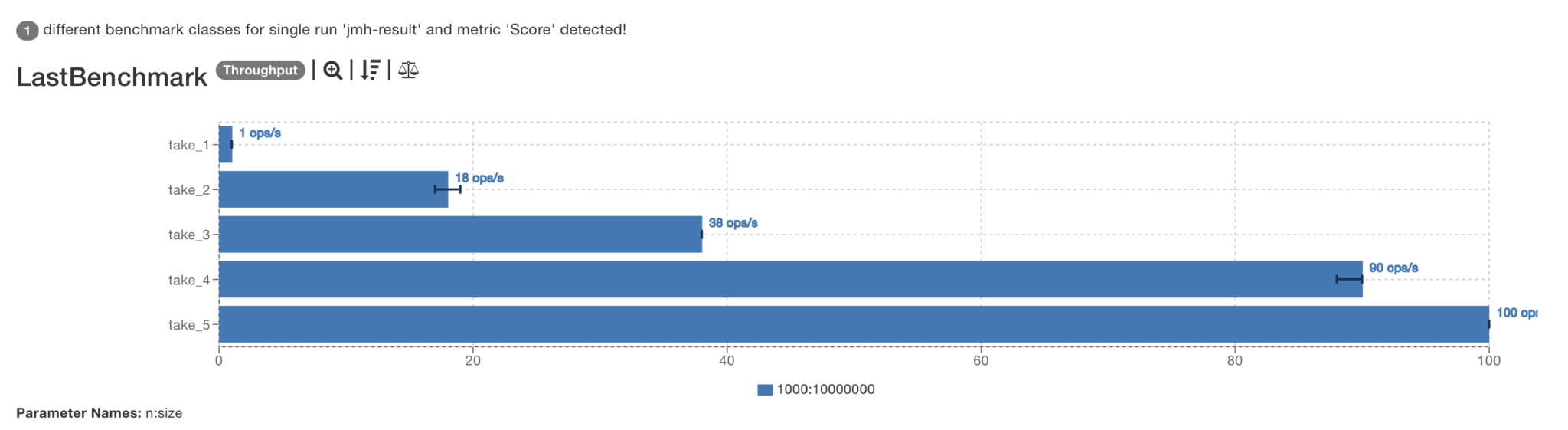

Benchmark (n) (size) Mode Cnt Score Error Units LastBenchmark.take_1 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 1,360 ± 0,216 ops/s LastBenchmark.take_2 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 19,060 ± 28,949 ops/s LastBenchmark.take_3 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 38,050 ± 8,296 ops/s LastBenchmark.take_4 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 84,340 ± 15,607 ops/s

Step 5: Make it Fast

We’ve now improved over 60 times! But could we do even better?

As you can see, AppendOnlyCircularBuffer.add method is the main bottleneck now (not counting Stream internals) and this is going to get tough now:

public void add(T element) {

buffer[endIdx++ % buffer.length] = element;

if (size < buffer.length) {

size++;

}

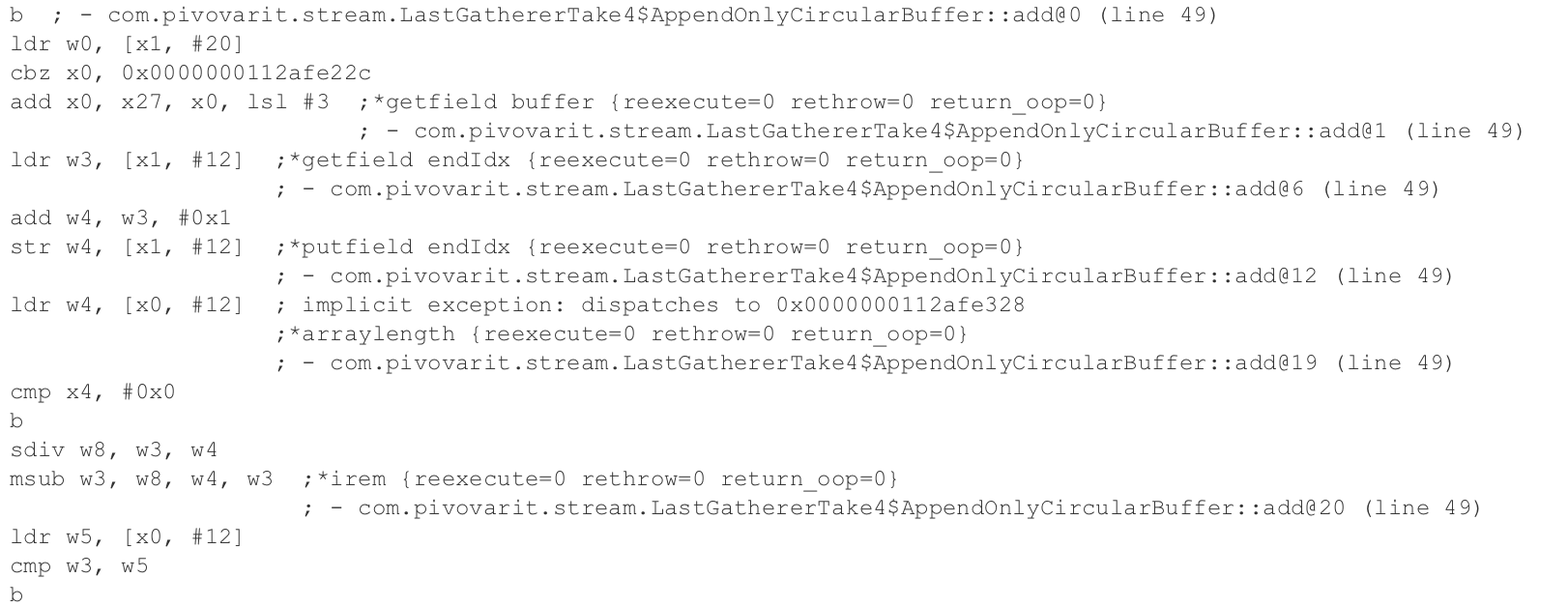

}This is pretty lean already, but let’s go deeper and look up the assembly code produced by JIT:

And the most relevant part:

0x0000000112afe244: sdiv w8, w3, w4

0x0000000112afe248: msub w3, w8, w4, w3 ;*irem {reexecute=0 rethrow=0 return_oop=0}Yes, it’s the modulo operation, which is implemented by a combination of two operations: sdiv and msub. According to Apple Silicon CPU Optimization Guide: 4.0, SDIV can take anywhere from 7 to 21 cycles and MSUB 1-2 cycles.

This is relatively expensive. Could we avoid paying this extra price?

One of the classic tricks involves replacing modulo operation with bit masking, but there’s a catch – it works only when modulus is a power of two. We can’t guarantee our modulus to be a power of two… or can we?

Nothing is stopping us from aligning our buffer’s size to the next available power of two. We’d just need to be careful to read last N elements properly.

First, we’d need to have an efficient method of finding it:

private static int nextPowerOfTwo(int x) {

int highest = Integer.highestOneBit(x);

return (x == highest) ? x : (highest << 1);

}Now, we’d need to use it to initialize buffer and a mask:

int capacity = nextPowerOfTwo(Math.max(1, this.limit)); this.buffer = new Object[capacity]; this.mask = capacity - 1;

Our add() method becomes:

void add(T e) {

buffer[writeIdx & mask] = e;

writeIdx++;

if (size < limit) {

size++;

}

}And we need a helper method for fetching an element at a given index:

T get(int index, int start) {

return (T) buffer[(start + index) & mask];

}void pushAll(Gatherer.Downstream<? super T> ds) {

int start = (writeIdx - size) & mask;

for (int i = 0; i < size && !ds.isRejecting(); i++) {

if (!ds.push(get(i, start))) {

break;

}

}

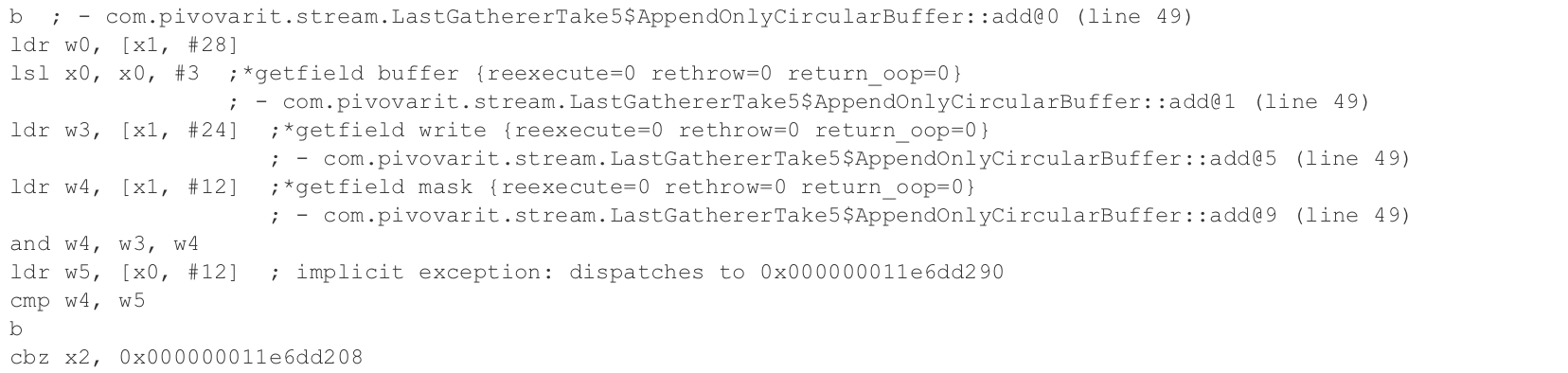

}We’re no longer relying on an expensive modulo operation, if we look up assembly produced by JIT, we can see that expensive instructions are gone, and we have a cheap AND(1-2 cycles) in their place:

Here’s the whole thing:

final class AppendOnlyCircularBuffer<T> {

private final Object[] buffer;

private final int mask;

private final int limit;

private int size;

private int writeIdx;

AppendOnlyCircularBuffer(int limit) {

this.limit = Math.max(0, limit);

int capacity = nextPowerOfTwo(Math.max(1, this.limit));

this.buffer = new Object[capacity];

this.mask = capacity - 1;

}

void add(T e) {

buffer[writeIdx & mask] = e;

writeIdx++;

if (size < limit) {

size++;

}

}

T get(int index, int start) {

return (T) buffer[(start + index) & mask];

}

void pushAll(Gatherer.Downstream<? super T> ds) {

int start = (writeIdx - size) & mask;

for (int i = 0; i < size && !ds.isRejecting(); i++) {

if (!ds.push(get(i, start))) {

break;

}

}

}

private static int nextPowerOfTwo(int x) {

int highest = Integer.highestOneBit(x);

return (x == highest) ? x : (highest << 1);

}

}Let’s finally run it and see the benchmarks!

Benchmark (n) (size) Mode Cnt Score Error Units LastBenchmark.take_1 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 1,352 ± 0,232 ops/s LastBenchmark.take_2 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 17,885 ± 14,921 ops/s LastBenchmark.take_3 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 38,229 ± 1,599 ops/s LastBenchmark.take_4 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 89,591 ± 18,486 ops/s LastBenchmark.take_5 1000 10000000 thrpt 3 100,454 ± 1,073 ops/s

This is where I genuinely run out of good ideas. I had a couple of them (like avoiding masking on each access), but benchmarks proved those were not as good as I had thought.

This is one of the most important takeaways here – performance optimisation cycle involves measuring, finding a bottleneck, forming a hypothesis and then evaluating it.

Step 6: Embracing Edge Cases

However, there’s still an important corner case to have a look at… a single last element lookup!

If all we care about is just the last element, then we can ditch the circular buffer and use a simple object wrapper:

record SingleElementLastGatherer<T>() implements Gatherer<T, SingleElementLastGatherer.ValueHolder<T>, T> {

@Override

public Supplier<ValueHolder<T>> initializer() {

return ValueHolder::new;

}

@Override

public Integrator<ValueHolder<T>, T, T> integrator() {

return Integrator.ofGreedy((state, element, _) -> {

state.value = element;

state.isSet = true;

return true;

});

}

@Override

public BiConsumer<ValueHolder<T>, Downstream<? super T>> finisher() {

return (state, downstream) -> {

if (state.isSet && !downstream.isRejecting()) {

downstream.push(state.value);

}

};

}

static class ValueHolder<T> {

private T value;

private boolean isSet;

}

}Benchmark results are now brutal:

Benchmark (n) (size) Mode Cnt Score Error Units circular_buffer 1 10000000 thrpt 3 100,963 ± 1,941 ops/s value_holder 1 10000000 thrpt 3 46678566,613 ± 340533,213 ops/s

So our ultimate solution is going to choose a strategy depending on the number of requested elements:

static <T> Gatherer<T, ?, T> last(int n) {

return switch (n) {

case 1 -> new SingleElementLastGatherer<>();

default -> new CircularBufferLastGatherer<>(n);

};

}And this is precisely what I’m doing in more-gatherers – library filling in the Stream API gaps.

Now, let’s benchmark this against a similar utility from gatherers4j:

Benchmark (n) (size) Mode Cnt Score Error Units gatherers4j 1 1000 thrpt 4 344953,593 ± 11157,945 ops/s more_gatherers 1 1000 thrpt 4 46403136,688 ± 919588,746 ops/s gatherers4j 1 10000 thrpt 4 35013,972 ± 386,535 ops/s more_gatherers 1 10000 thrpt 4 45112509,001 ± 259866,835 ops/s gatherers4j 1 100000 thrpt 4 3480,072 ± 295,102 ops/s more_gatherers 1 100000 thrpt 4 52938383,744 ± 843270,687 ops/s gatherers4j 1 1000000 thrpt 4 349,321 ± 12,975 ops/s more_gatherers 1 1000000 thrpt 4 46070928,929 ± 328021,478 ops/s gatherers4j 1 10000000 thrpt 4 34,992 ± 1,383 ops/s more_gatherers 1 10000000 thrpt 4 45576656,184 ± 603781,325 ops/s Benchmark (n) (size) Mode Cnt Score Error Units gatherers4j 10 1000 thrpt 4 335775,631 ± 19864,798 ops/s more_gatherers 10 1000 thrpt 4 638157,379 ± 89987,065 ops/s gatherers4j 10 10000 thrpt 4 34660,535 ± 3070,990 ops/s more_gatherers 10 10000 thrpt 4 89377,421 ± 745,692 ops/s gatherers4j 10 100000 thrpt 4 3514,937 ± 97,364 ops/s more_gatherers 10 100000 thrpt 4 9980,622 ± 87,814 ops/s gatherers4j 10 1000000 thrpt 4 346,090 ± 9,348 ops/s more_gatherers 10 1000000 thrpt 4 630,170 ± 81,201 ops/s gatherers4j 10 10000000 thrpt 4 33,716 ± 8,170 ops/s more_gatherers 10 10000000 thrpt 4 99,399 ± 3,150 ops/s Benchmark (n) (size) Mode Cnt Score Error Units gatherers4j 100 1000 thrpt 4 338606,915 ± 30009,425 ops/s more_gatherers 100 1000 thrpt 4 920026,588 ± 5509,723 ops/s gatherers4j 100 10000 thrpt 4 34730,669 ± 1584,566 ops/s more_gatherers 100 10000 thrpt 4 88842,806 ± 1361,405 ops/s gatherers4j 100 100000 thrpt 4 3370,974 ± 717,176 ops/s more_gatherers 100 100000 thrpt 4 9979,804 ± 135,956 ops/s gatherers4j 100 1000000 thrpt 4 308,239 ± 4,847 ops/s more_gatherers 100 1000000 thrpt 4 989,730 ± 7,982 ops/s gatherers4j 100 10000000 thrpt 4 32,684 ± 0,397 ops/s more_gatherers 100 10000000 thrpt 4 98,816 ± 1,606 ops/s Benchmark (n) (size) Mode Cnt Score Error Units gatherers4j 1000 1000 thrpt 4 270321,525 ± 2961,567 ops/s more_gatherers 1000 1000 thrpt 4 606415,730 ± 2780,339 ops/s gatherers4j 1000 10000 thrpt 4 31727,683 ± 122,620 ops/s more_gatherers 1000 10000 thrpt 4 101115,273 ± 370,316 ops/s gatherers4j 1000 100000 thrpt 4 3241,063 ± 9,743 ops/s more_gatherers 1000 100000 thrpt 4 8857,406 ± 52,233 ops/s gatherers4j 1000 1000000 thrpt 4 323,806 ± 3,993 ops/s more_gatherers 1000 1000000 thrpt 4 998,388 ± 13,033 ops/s gatherers4j 1000 10000000 thrpt 4 32,250 ± 0,205 ops/s more_gatherers 1000 10000000 thrpt 4 98,674 ± 0,897 ops/s

Benchmarked on MacBook Pro Nov 2023 with Apple M3 Pro with 36GB RAM and Tahoe 26.2.

The code supporting this article along with benchmarking suite and full results can be found on GitHub. Here’s the more-gatherers library that features this Gatherer implementation.